Push to End Prison Rapes Loses Earlier Momentum

- Deborah Sontag

- May 12, 2015

- The New York Times

NEW BOSTON, Tex. — The inmate, dressed in prison whites with a shaved head and incongruously tender eyes behind wire-rimmed glasses, entered the visiting room with her wrists joined as if she were handcuffed. At 31, she had spent her whole adult life behind bars, and it looked like a posture of habit.

She introduced herself: “My given name at birth was Joshua Zollicoffer, but my preferred name is Passion Star.”

A transgender woman whose gender identity has been challenged by the Texas authorities, Ms. Star herself is challenging Texas’ refusal to accept new national standards intended to eliminate rape in prison, which disproportionately affects gay and transgender prisoners. Last spring, Gov. Rick Perry declared in a letter to Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. that Texas had its own “safe prisons program” and did not need the “unnecessarily cumbersome and costly” intrusion of another federal mandate.

Ms. Star, who says she is a victim of repeated sexual harassment, coercion, abuse and assault in Texas’ maximum-security prisons for men, disagrees.

“Look, I got 36 stitches and have scars on my face that prove the prisons are not safe and the current system does not work,” she said. “Somebody needs to be intrusive into this state’s business. Because if somebody was intruding, probably these things would not happen.”

After decades of societal indifference to prison rape, Congress, in a rare show of support for inmates’ rights, unanimously passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act in 2003, and Mr. Perry’s predecessor as governor, President George W. Bush, signed it into law.

“The emerging consensus was that ‘Don’t drop the soap’ jokes were no longer funny, and that rape is not a penalty we assign in sentencing,” said Jael Humphrey, a lawyer with Lambda Legal, a national group that represents Ms. Star in a federal lawsuit alleging that Texas officials failed to protect her from sexual victimization despite her persistent, well-documented pleas for help.

But over 12 years, even as reported sexual victimization in prisons remained high, the urgency behind that consensus dissipated. It took almost a decade for the Justice Department to issue the final standards on how to prevent, detect and respond to sexual abuse in custody. And it took a couple of years more before governors were required to report to Washington, which revealed that only New Jersey and New Hampshire were ready to certify full compliance.

With May 15 being the second annual reporting deadline, advocates for inmates and half of the members of the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, a bipartisan group charged with drafting the standards, say the plodding pace of change has disheartened them despite pockets of progress.

“I am encouraged by what several states have done, discouraged by most and dismayed by states like Texas,” said Judge Reggie B. Walton of United States District Court for the District of Columbia, who was appointed chairman of the now-disbanded commission by Mr. Bush.

Some commissioners fault the Justice Department for failing to promote the standards vigorously. Others blame the correctional industry and unions for resisting practices long known to curb “state-sanctioned abuse,” as one put it. All lament that Congress has sought to weaken the modest penalties for noncompliance, and that five governors joined Mr. Perry last year in snubbing the standards.

“There’s a whole kind of backlash, which is very depressing,” said Jamie Fellner, a former commissioner who is senior counsel for the United States program of Human Rights Watch. “It’s 12 years since the law passed. I mean, really. We’re still dealing with all these officials saying, ‘Trust us. We’ll take care of it’?”

Last year, 42 governors signed a form providing “assurance” to the Justice Department that they were advancing toward compliance. But they were allowed to make that assurance without having conducted any outside audits; the commissioners protested this in a letter to Mr. Holder in November, expressing concern about “efforts to delay or weaken” adherence to the standards.

In fact, the ambitious goal to audit every prison, jail, detention center, lockup and halfway house in this country over a three-year period is far behind schedule.

Some 8,000 institutions are supposed to be audited for sexual safety by August 2016, but only 335 audits had been completed by March, according to a Justice Department document obtained from the office of Senator John Cornyn of Texas; the department declined to provide numbers.

The Justice Department said it “remains steadfast in its commitment to the implementation of the National PREA Standards” — PREA is the acronym for the Prison Rape Elimination Act — and hopes for “full participation” from all states this year.

But states face only a small penalty, the loss of 5 percent of prison-related federal grants, if they opt out of the process entirely. “There are a lot of carrots in PREA, and not enough sticks,” said Brenda V. Smith, an American University law professor and another former commissioner.

Texas forfeited $810,796 — a minuscule fraction of its multibillion-dollar corrections budget — after Mr. Perry declined to sign an assurance letter. According to a spokesman for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, this loss “will not have any effect on T.D.C.J. operations.”

The other renegade states, as advocates called them, were Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Indiana and Utah.

Texas’ opting out was considered especially significant, however, because it has the largest prison population in the country and by far the most reports of sexual assault and abuse. Texas had three and a half times as many allegations as California in 2011, when California still had more inmates than Texas, according to the federal data.

The Texas authorities attribute this to “extensive efforts to encourage and facilitate reporting.” Declining to discuss Ms. Star’s case, they said their “goal is to be as compliant as possible with PREA standards without jeopardizing the safety and security of our institutions.”

Twenty-seven of their 109 prisons have passed outside audits, they said, including the one where Ms. Star is now locked up for a teenage offense that the authorities considered kidnapping.

A Predatory Culture

In this rural area just west of Texarkana, the Barry B. Telford prison complex sits behind chain-link fences topped with coils of razor ribbon. It is where Ms. Star began her incarceration the year that Congress passed the prison rape law and where, after an odyssey through six other prisons, she unexpectedly returned at the end of March.

She is used to moving around. Born in Mississippi in late 1983, Ms. Star lived the peripatetic life of a military child, shuttling from state to state and twice to Germany before settling near Fort Hood, Tex., as a teenager.

On a summer day when she was 18, she accompanied her boyfriend, who was 23, to a Chevrolet dealership to test-drive a car. Her boyfriend took the wheel of a maroon Impala, a salesman got in the front passenger seat and Ms. Star sat in the rear.

When the salesman indicated it was time to return to the lot, the boyfriend said no, in Ms. Star’s recounting.

“I’m like, ‘Wow. What do you mean?’” she said. “And he’s like, ‘Be quiet.’ It was one of those things where keeping it real goes wrong. Where I could have been like, ‘Well, you need to stop,’ or gotten out, and I didn’t. We make bad decisions when we’re young.”

After 40 miles, they deposited the salesman on a rural road. He eventually flagged down a police car, and an alert was issued for the stolen Chevy. The couple kept driving north, even picking up a hitchhiker at one point, until, with the authorities in pursuit, their flight ended in a ditch.

Charged with aggravated kidnapping, a first-degree felony that carries a penalty of five to 99 years, Ms. Star accepted the same plea deal of 20 years as her boyfriend.

“The law applies a rule of parties, which allows them to charge the passenger with the same level of culpability as the primary actor,” said M. Bryon Barnhill, who was Ms. Star’s court-appointed lawyer. But, he added, the boyfriend (and the hitchhiker) told the authorities “they were acting in concert with the intention of stealing the car and traveling to Canada to start a new life.”

Ms. Star was 19 when she arrived at Telford, with no possibility of parole for a decade. She was quickly inducted into a gang-ruled world with an ultimatum, she said: “You’re going to ride with us, or you’re going to fight.”

“In the state of Texas, in the general population, there is a culture where gay men and transgender women in prison are basically preyed on by the stronger inmates,” she said. “They have to be the property of a person who’s in a gang, and this person is the individual who speaks for them. So basically, they’re coerced into being sexually active to survive.”

Ms. Star said that after complaining fruitlessly to prison employees, she submitted to a coerced sexual relationship. She tried to leave the inmate once, she said, but he choked her in response.

The most recent national inmate survey by the Justice Department found that sexual victimization was reported by 3.1 percent of heterosexual prisoners, 14 percent of gay, lesbian and bisexual prisoners and 40 percent of transgender inmates.

Because gay and transgender inmates are at such high risk, a prison’s efforts to protect them are seen by experts as a barometer of its commitment to eliminating rape. That is why Ms. Star’s advocates believe her case represents a pervasive problem in Texas; those defendants who filed a legal response to her complaint deny all allegations against them and contend they acted “in good faith.”

In her early years in prison, Ms. Star considered herself gay. She knew she was “additionally different,” but it would take a few more years for her to identify as a transgender woman, to adopt a “feminine alias” and to start feeling comfortable in her own skin.

“You know how penguins are?” she asked. “On land, if you look at a penguin when it walks around, it’s just an ungainly, clumsy creature. But in water, a penguin is one of the most graceful animals in the world.” She added, “I didn’t feel like I was in my element until, at all types of personal risk to myself, I became Passion.”

Becoming Passion in a maximum-security men’s prison in Texas was not easy. “Basically, they frown on us expressing our gender,” she said. “I did at one point wear my hair longer, arch my eyebrows, shave my legs and my body and everything. I wore small, form-fitting clothes and made myself feminine underwear. But I was actually disciplined for it.”

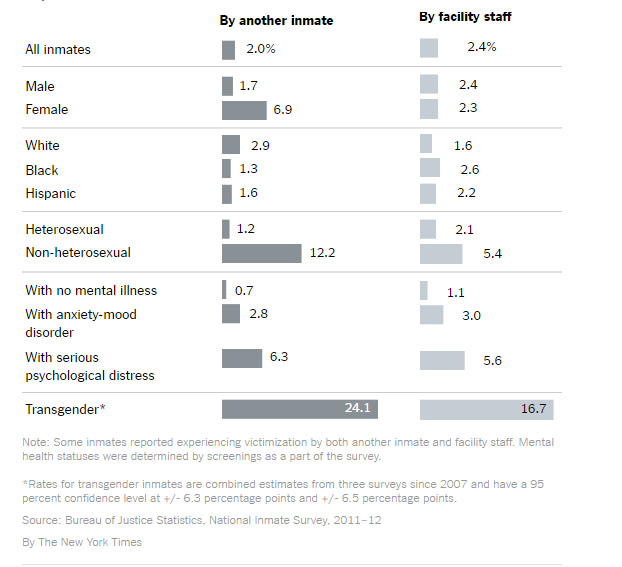

Sexual Victimization in Prison

The share of state and federal prison inmates who reported experiencing sexual victimization in the past year, according to a survey conducted from February 2011 to May 2012.

It was only in 2014 that she learned from a notice in the prison newspaper that inmates were allowed to request classification as transgender, she said, and she did so.

But in their response to her lawsuit, Texas officials refer to Ms. Star as Mr. Zollicoffer, use male pronouns and “deny” she is transgender, “as no such medical diagnosis has been made.”

“If she were seeking medical care — and she does intend to transition, but until now she has been in survival mode — a diagnosis could be relevant,” Ms. Humphrey, her lawyer, said. “But whether or not she was diagnosed as transgender has nothing to do with whether or not she deserves protection from sexual assault.”

‘The Day-to-Day Horror’

As a researcher who studied prison rape when nobody wanted to know about it, Cindy Struckman-Johnson, a social psychologist at the University of South Dakota, was astonished when Congress passed the rape legislation.

“To me, it was like a miracle,” said Ms. Struckman-Johnson, a former commissioner who described how she had become “persona non grata” in Nebraska in the 1990s after finding a high rate of prison rape there. “Ever since PREA, nobody can really be in denial.”

The law described prison rape as epidemic. Ideologically evenhanded, it referred at once to “the day-to-day horror of victimized inmates” and to “brutalized inmates more likely to commit crimes when they are released.” It spoke of the potential spread of H.I.V. and of the need for Congress to protect the constitutional rights of prisoners in states where officials displayed deliberate indifference.

The law, which established the commission, laid out a timetable under which the attorney general would publish the final antirape standards by 2007.

But after eight public hearings, 11 site visits and two public comment periods on draft standards, the commission did not release its final report and proposed standards until 2009.

“What took so long?” Ms. Smith, the American University law professor, asked. “Resistance was coming from and still is coming from many correctional agencies. The resistance was: This is going to cost us too much money. But also, we were developing standards not just around preventing rape, but around respect and dignity and changing the culture that permitted or even encouraged rape in custody.”

It then took the Justice Department three additional years to issue final standards that were in the end “almost identical — very frustrating,” one commissioner said.

The 52 standards for prisons and jails apply to everything from hiring and staffing levels to investigation and evidence collection to medical treatment and rape crisis counseling.

State officials found some standards particularly intrusive. Mr. Perry protested that limitations on cross-gender strip searches, pat downs and bathroom supervision would force Texas to discriminate against its female officers. He said the requirement that youths in adult prisons be “separated by sight and sound” from grown-up inmates infringed on Texas’ right to set its age of criminal responsibility at 17.

Training and technical assistance related to the coming regulations began in 2004. Since 2011, the Justice Department has doled out some $31 million in PREA-related grants, and tens of millions more to set up and run the National PREA Resource Center.

And indeed, judged through a long lens, considerable progress has been made. That wardens across the country now profess zero tolerance for sexual abuse represents a cultural transformation itself. There are antirape posters on prison bulletin boards, hotlines to report sexual abuse, educational videos for inmates, and training sessions for guards. Statistics show some prisons and jails with very low or even no reported sexual abuse.

“I’m not on the top deck, I’m in the engine room with Scotty, and I see behavioral change on the yards and in the cellblocks,” said James E. Aiken, a correctional consultant and former commissioner. “This is not a speedboat; it’s a very big ship.”

John Kaneb, a business executive and former vice chairman of the commission, said he also thought “things are going well now.”

Over 500 specialized auditors have been certified, and, he said, the pace of audits is accelerating: “They’re not going to get 8,000 done in the next 15 months, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they had 1,000 done by end of year.”

Yet others are disappointed that the states are moving slowly and that the Justice Department declines to say how much longer it will allow governors to provide “assurances” instead of certifying compliance.

“This leaves open the absurd possibility that a state could kick the can down the road in perpetuity without ever incurring a financial penalty,” said Lovisa Stannow, the executive director of Just Detention International.

Pat Nolan, director of the Center for Criminal Justice Reform at the American Conservative Union Foundation and a former commissioner, said that Mr. Perry’s public challenge to the standards caused ripples of anxiety that linger.

“The fear is that if you get enough states thumbing their nose at this, the whole thing could unravel,” he said.

In the end, the former commissioners said, oversight might have to become the provenance of the courts.

“I think that’s the greatest hope, that the standards become the legal standards of care,” Judge Walton said. “If states realize they’re going to have multimillion-dollar lawsuits, that will be an incentive for them.”

A Quest for ‘Safekeeping’

At Lambda Legal’s offices on Wall Street, not long after Mr. Perry’s declaration to Washington, Ms. Humphrey started combing through letters from inmates complaining about sexual abuse.

“I was looking in our mailbag for a plaintiff who could illustrate the problems Texas was having,” Ms. Humphrey said. “And there she was.”

What Ms. Humphrey found was a thick envelope from Ms. Star containing the proposed draft of a legal complaint along with medical files, grievance reports and appeals — a meticulous record of her years behind bars.

In 2006, Ms. Star was transferred to the James V. Allred Unit in Wichita Falls.

Allred would soon be singled out by the Justice Department as one of the 10 most sexually violent prisons in the country. Five of the 10, in fact, were in Texas, and Ms. Star would end up doing time in three of them.

At Allred, she was immediately targeted because she had been at Telford, she said, but she was older and unwilling “to lay down and accept these things happening to me.”

So she embarked on what became her unrelenting quest to be placed in “safekeeping,” which is what Texas calls separate housing units for vulnerable inmates. She sought safekeeping not only because of recurrent sexual harassment, coercion and threats of violence, but also because of retaliation for reporting these incidents — from staff members as well as inmates, she said.

At Allred, when she told a prison official she feared for her life after refusing sexual demands, the official told her she would be fine because she is black, she claims in her lawsuit. Over the years, she came to believe the system’s protection program was racially discriminatory.

A racial breakdown of the inmates in safekeeping, provided by Texas, indicates she may have had a point. Of the 1,569 inmates with that status now, 57 percent are white, while whites constitute 30 percent of the inmate population. Twenty-three percent in safekeeping are black, compared with 35 percent over all, and 19 percent are Hispanic, compared with 33 percent.

In March 2007, Ms. Star was assigned to a cell with a gang member who instantly started demanding sexual favors. She informed a guard and asked for help, she said. Two days later, the cellmate raped her at knife point. After she reported the attack, he threw a fan at her head. It was the “worst moment of my life,” she said, making her feel “utterly powerless,” briefly suicidal and extremely fearful “it would happen to me again and again.”

Ms. Star said she did not know what happened to her cellmate after she went to the infirmary to be treated; under the standards, victims are supposed to be kept apprised.

A national panel, established after the rape law to examine institutions with the best and worst records, visited Allred and could find no indication that any sexual abuse claims had been substantiated. It noted that a significant number of claims had been filed by gay inmates — “whom staff members referred to as queens.”

“A question remains as to whether complaints from homosexual inmates are treated as seriously as they deserve,” the panel said of Allred.

Texas has a very low rate of substantiating allegations. Of 743 reports of sexual assault and abuse in the 2013 budget year, 20 cases, or 2.7 percent, were corroborated; the national rate is 10 percent. One prison rape case was sent to a grand jury that year.

After the rape, Ms. Star was moved into “protective custody,” a form of solitary confinement that the standards say should be used for rape victims only short-term and if no alternative, such as safekeeping, is available.

Two weeks later, Ms. Star was transferred to a third prison, where her new cellmate made her watch him masturbate, she said.

“I freaked,” she said. “Immediately, I was like, ‘I can’t deal with this.’ For a long time, I bounced from cell to cell, cell to cell, cell to cell. And that’s when the tag ‘snitch’ started to stick to me, because I was complaining constantly about people trying to force me into things.”

She said that over the years, some prison officials had called her “faggot” and “punk”; others blamed her for bringing problems on herself. One suggested, using language that cannot be printed, that she perform oral sex, “fight or quit doing gay” stuff, her lawsuit says.

In her fourth and fifth prisons, Ms. Star’s complaints of continuing abuse and assault were dismissed with “formulaic” responses, her lawsuit says.

In denying her requests for safekeeping, Texas made references to her “assaultive history,” suggesting she could endanger other vulnerable inmates. Ms. Star says that her disciplinary history “is a direct reflection of T.D.C.J.’s not protecting me.”

“I have a disciplinary history for defending myself three or four times over 13 years,” she said. “I’ve never hurt anybody. But I’ve been hurt.”

Ms. Star was also denied parole — though her former boyfriend and co-defendant was released in April 2013, something Ms. Star learned in the interview.

“Wow,” she said. “That kind of makes me want to cry.”

On Nov. 19, 2013, with threats against her mounting, Ms. Star filed an emergency grievance appealing the most recent denial of her request for safekeeping. The next morning, heading to breakfast, Ms. Star found her path blocked by gang members. One repeatedly slashed her face with a razor. This was the attack that required the 36 stitches.

After that, she was transferred to her sixth prison. The same problems ensued. Begging again for safekeeping, Ms. Star wrote in a grievance: “Just recommending that I be transferred to another unit will not ensure my safety, just as it did not after the 3-29-07 sexual assault, nor after the 11-20-13 assault with a weapon. I am an offender with a ‘potential for victimization,’ otherwise I wouldn’t be constantly victimized and threatened by other offenders.”

This time, somebody listened. The prison’s classification committee agreed she should be put in safekeeping. The state, however, overruled it.

By this point, Ms. Star had been reaching out beyond prison walls — writing to the state-level corrections officials as well as to civil rights and advocacy groups, which report that they get more reports of sexual abuse from inmates in Texas than anywhere else.

“Passion is hardly alone, but she is incredibly intelligent, incredibly well organized, and her perseverance is unparalleled,” Ms. Humphrey said.

After the lawyer’s first visit with Ms. Star last summer, Ms. Star was moved into protective custody and spent 110 days in an 80-square-foot cell. Her lawsuit alleges that Texas officials “use confinement in isolation and the threat of isolation to deter people in custody from complaining about sexual abuse, threats and other assaults.”

Last November, Ms. Star was transferred to her seventh prison, William P. Clements, another prison with a very high rate of sexual victimization. She immediately found herself back among gang members she knew and encountered escalating threats of assault and rape.

In March, her lawyers filed an emergency motion asking that the court order Texas to place her in safekeeping or explain how it would otherwise keep her safe.

“I’m afraid Passion is going to get murdered — like this weekend,” Ms. Humphrey said then.

For that weekend, her lawyers agreed to let the authorities place Ms. Star back in solitary confinement while they negotiated a resolution. At that point, Texas appeared to be arguing that Ms. Star’s only alternative was to remain in isolation.

On March 20, The New York Times asked Texas for permission to interview Ms. Star.

On March 30, more than a decade after she says she first requested it, Texas put Passion Star in safekeeping. Her lawsuit, which seeks damages from the officials who allegedly failed to protect her, is continuing.

At the time of the interview, she had been in safekeeping only a couple of days, but already found the new atmosphere a relief. “Everybody’s calmer,” she said. “The tension level is extremely low. There are no gang influences that basically are threatening our lives. So it’s a change — a change for the better.”

As a reporter left the prison that day, an officer at the security entrance said, “So, did you see him-her?”

Fumbling for an answer, the reporter said yes, and that Ms. Star had been “very nice.”

“For a kidnapper,” the officer replied.

Originally posted here